The changing climate

"[A] considerable change of climate, inexplicable at present to us, must have taken place in the Circumpolar Regions, by which the severity of the cold that has for centuries past enclosed the seas in the high northern latitudes in an impenetrable barrier of ice has been during the last two years, greatly abated."

―President of the Royal Society, to the Admiralty, 20 November 1817 [1]

"Ragavis [1809–1892] accusses Strabo [c. 63 BC – c. 24 AD] of inaccuracy, because the latter said that the river [Kephisos of Attica] is dry during summer, when in fact its flow is perrenial. When I came to Greece, just before the regime change-over [probably 1877], I found that Ragavis was right and Strabo was wrong, for there was no time of the year when Kephisos was without water. While I did not make measurements of its depth, I perfectly remember that, when at its lowest, the water would cover a quarter of my horse's legs, and when higher it would reach mine; and many times, while passing through Sepolia, I happened to be caught in a blocking maze of intertwined streams. These days of old glory are now forgotten and today the river is almost always dry."

―Emmanouel Roides, The countryside of Athens, 1897

"There are ominous signs that the earth's weather patterns have begun to change dramatically... A survey completed last year by Dr. Murray Mitchell of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reveals a drop of half a degree in average ground temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere between 1945 and 1968."

―Peter Gwynne, The cooling world, Newsweek, 28 April 1975 [2]

The average temperature of the Earth, it is claimed, has increased by 0.7°C during the last 100 years, and this, it is also claimed, is the result of man-made global warming.

It is important to understand that the Earth has no such hole in which you can stick a thermometer and take a reading. Determining the so-called average temperature of the Earth is a very complicated business. You need to use measurements of temperatures wherever those exist, and make assumptions about how to average them over areas. In addition, 0.7°C is a very low variation, barely over the accuracy range of conventional thermometers. If you have measurements from 1850 to 1950 in a location, it is not the same thermometer that was used throughout that period; and even the same thermometer might produce slightly different measurements during its life; and differences in the weather station installation, such as painting its enclosing box or the changing vegetation, also have an effect. This means that you have to go into very complex studies, comparing measurements with those in nearby locations (which also, of course, suffer from the same problems), and doing appropriate calibrations. It can be difficult to reach an accuracy of 0.7°C.

Even if you solve these problems, and you can safely arrive at the conclusion that your measurements do indicate a temperature increase, it is by no means easy to generalize to the Earth average. Maybe the earth has heated up and the sea has cooled down; maybe Europe and North America (where there are many measuring stations) have heated up and Africa has cooled down. Maybe the Northern Hemisphere has heated up and the Southern has cooled down. In addition, thermometers are usually located near urban areas, and urbanisation does cause a local temperature increase, which, however, is not necessarily an indication of a global temperature increase. Since 1978, another means of measuring global temperature is with satellites, but this is also indirect and involves assumptions and calculations. Therefore, the alleged average global temperature increase, rather than fact, is an estimation.

We cannot tell you whether the estimation is good or bad, because we have not examined it; but in any case, 0.7°C in 100 years is a quite reasonable change, not especially worthy of much notice. The Earth's temperature has never stayed the same. A change of 0.7°C in a century is not unusual and it does not indicate a permanent trend any more than does a difference in temperature between yesterday and today.

Imagine that you are a housefly born in Athens, Greece, in 15 July. Houseflies normally live up to 25 days, but you have an exceptionally long life and you die in 15 August. During your life, some days are hot, about 35―36°C, some are cool, about 29―30°C, and so you experience a large and interesting range of temperatures. It is 11 August, and you even remember an event that happened in your early days, in 17 July, of water falling from the sky, which had forced you to stay hidden. You are the oldest housefly around and you tell stories about that to the younger ones.

Then, on 12 August, a heat wave strikes Athens, raising the temperature to 39°C. On 13 August it is 41°C, and on the 14th it has reached 42°C. By human standards, this is quite usual; such a heat wave happens in Athens almost every year. But you are a housefly, and you have never seen anything like that. "Never in my life have I seen such heat!", you exclaim; and you are tempted to think that the climate is changing in an unusual manner, and that the world is coming to an end.

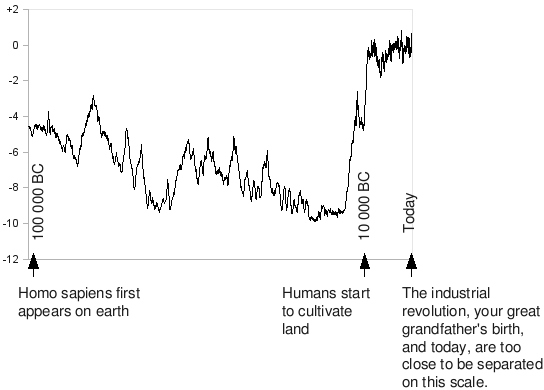

Now imagine that you are a being as old as humanity itself. Humans are thought to inhabit this planet something like 100 thousand years. Figure 1 shows how the temperature has changed during these 100 thousand years.

Figure 1: Approximate average Earth temperature in the last 100 thousand years (difference from today in °C)

How do we know?

How do we know that humanity is 100 thousand years old? There are several techniques that can be used to estimate the age of an old item such as a fossil or an artifact; such techniques are dendrochronology, radiocarbon dating, and pottasium-argon dating. For the sake of brevity we won't go into detail; you can find information about them in books (e.g. [3]) or by searching the web. Archaelogists and palaeontologists use such techniques to collect evidence and make rough estimations. The exact date of the appearance of Homo Sapiens is unknown, but it is thought to be some time between 500 thousand and 75 thousand years ago [3].

How do we know the evolution of earth temperature during the last hundred thousand years? In Antarctica and Greenland a new layer of ice is added each year, covering the ice of the previous year. These places have one long night and one long day each year, and the night ice is slightly different than the day ice, resulting in slightly different colours. We can therefore see horizontal stripes in ice columns extracted by drilling, and each stripe is one year. There are two complementary ways to determine the temperature of each year. First, as when you put frozen food in the oven, it warms outside but is still cold inside, the Antarctic ice retains its internal temperature as it was thousands of years ago. Second, oxygen atoms normally have 8 protons and 8 neutrons, but there is also an isotope with 10 neutrons, called oxygen-18, and the quantity of oxygen-18 in snow depends on the temperature during the snowfall. By determining the content of oxygen-18 in ice we can estimate the temperature during snowfall. These two techniques are used together, for verification and calibration of one another [4]. Results are good, but they also depend on the unproven assumption that the average temperature of the Earth moves together with the average temperature of the poles.

So, yes, the climate is changing. It is changing all the time. It is changing from minute to minute (although in this case we call it "weather"), from year to year, from century to century, and from millenium to millenium. If your 100-year-old great grandfather tells you that the climate is different now than it was in his early days, this is no suprise. The climate is probably not as different as he thinks, because human memory is very selective and far from objective, but at the same time it is an undeniable truth that climate has always been changing, in all time scales.

Next: The climate models

References

| [1] | Minutes of Council, Volume 8. pp.149-153, Royal Society, London, 1817; http://www.john-daly.com/polar/arctic.htm, accessed on 2009-04-06. |

| [2] | http://www.denisdutton.com/cooling_world.htm, accessed on 2009-04-21. |

| [3] | (1, 2) Brian M. Fagan, "Time", in Archaeology: A Brief Introduction, Fourth Edition, HarperCollins, 1991, pp. 51–72. |

| [4] | Holli Riebeek, "Paleoclimatology: The Ice Core Record", 2005; http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/Paleoclimatology_IceCores/, accessed on 2009-04-21. |